By: Karthik Sastry

Historians have not always been kind to me. In his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon called me “the common enemy of mankind,” conquering to spread “rapine and cruelty.” In this essay, I hope to set the record straight; during my reign (211 A.D. – 217 A.D.), I pursued many meaningful reforms that helped sustain the Roman Empire in its latter stages. I tried to usher in a new age of glory for Rome with my grander plan of uniting all of Europe and perhaps even Asia under one rule. I could have surpassed even the immortal Alexander—only for my dreams to be cut short by one sweep of the blade.

Historians have not always been kind to me. In his book The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon called me “the common enemy of mankind,” conquering to spread “rapine and cruelty.” In this essay, I hope to set the record straight; during my reign (211 A.D. – 217 A.D.), I pursued many meaningful reforms that helped sustain the Roman Empire in its latter stages. I tried to usher in a new age of glory for Rome with my grander plan of uniting all of Europe and perhaps even Asia under one rule. I could have surpassed even the immortal Alexander—only for my dreams to be cut short by one sweep of the blade.Born Lucius Septimius Bassianus on April 4, 188, I was destined to be the emperor of Rome. I later gained the nickname “Caracalla” from a style of cloak I often wore. I despised education. From an early age, I developed a passion for military life, accompanying my father’s campaigns on many occasions. For me, the world of books seemed frivolous; the true glory was on the battlefield, where history’s greatest figures proved their leadership and determination.

In 211, my father died leaving the empire to my brother Geta and me. It was painfully apparent, however, that this arrangement could never last. Under joint leadership, a civil war would be inevitable; two people could not share the responsibility of the empire in an equitable way. Thus, I took decisive action and did what need to be done. To maintain stability, it was also necessary to quell the dissent in Rome that threatened the integrity of the empire and issue a damnatio memoriae on my brother. It was for the sake of the empire; Geta could not have ruled the empire by himself.

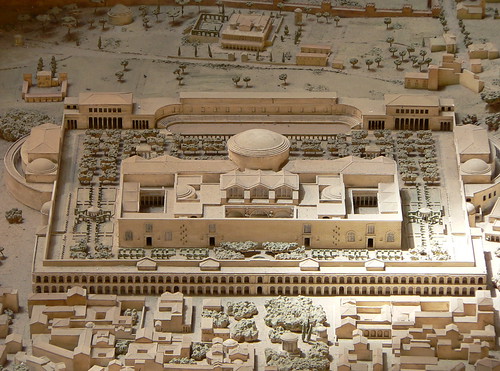

Arguably, my greatest accomplishment was the Constitutio Antonianiana, an edict extending citizenship to all freedmen in the Roman Empire. Some historians have characterized this as a selfish measure to increase taxation and generate more money for lavish building projects. And I concede that its primary aim was to the money supply for the government. But the reality of the time was that the Roman Empire was no longer focused solely on Rome; I realized that the future of Rome hinged on the ability to maintain and further integrate outlying areas. Thus, non-Romans needed representation. Additional revenue was also beneficial to the overall health of the Empire; by taxing the entire Empire, Rome had enough capital to provide for the entire Empire. In addition, I constructed a massive bath complex in Rome to benefit the people. Unlike the purely selfish building projects of previous empires (such as pleasure palaces), my thermae were perfectly reasonable. Their opulence maintained the standard that Rome set to be the greatest city in the world.

Some of critics portrayed me as insecure and superstitious throughout my reign. I was certainly involved in several religious movements, including the cults of Mithras and Serapis. But my religious interests were only a function of the changing times. Many Romans were beginning to lose confidence in our nation’s traditional religious beliefs. These so-called mystery cults provided a means of escape from the mundane realities of state religion. They simply had a stronger message, with more concrete explanations of the nature of the body and the soul. Roman religion was an antiquated relic of the past; these deities were the future.

Militarily, I gained the support of my legionaries by increasing the pay of soldiers to 675 denarii. I made two major campaigns, one in Gaul (212-213) and one in Parthia (216-217). Some criticized my war tactics as brutal. War is, by definition, a brutal act. In the battle of Issus, the Macedonians killed 20,000 enemies in battle and ordered the remaining prisoners to be killed. Absolute victory only comes with bold and assertive strategies; I did what I had to do. In Parthia, I hoped to expand the Roman Empire even further eastward into Asia. Only by conquering Asia could I achieve my dream of replicating the greatness of Alexander. But just as glory was within my grasp, a member of my own guard felled me with his sword. Commoners never realize the immense pressures and expectations of being an emperor. When faced with tough choices, I had to make decisions. Unfortunately, I alienated myself from my enemies in the process.

wow karthik. thats absurdly long. ive had enough

ReplyDelete